Aníbal/Salamanca is a tribute to Aníbal Núñez (Salamanca, 1944-1987), a poet who recorded the transformation that Castile underwent from the 1960s onwards, especially the modernising impact that swept away nature and urbanised the countryside. On the other hand, with a style that swings between irony and lyrical exaltation, he also explored the problematic relationship between language and reality.

Starting from his texts in a literal way, David Bestué proposes a sculptural edition based on the mixture of some of the ingredients of his poetry. On the one hand, the form is given by a brick collected in Tejares, a village the poet spoke of and which last century was transformed into a peripheral neighbourhood of the Salamanca capital. The “mud” of this brick is a mixture of flowers and fruits from the same apple tree, agglutinated with mud from the Tormes River.

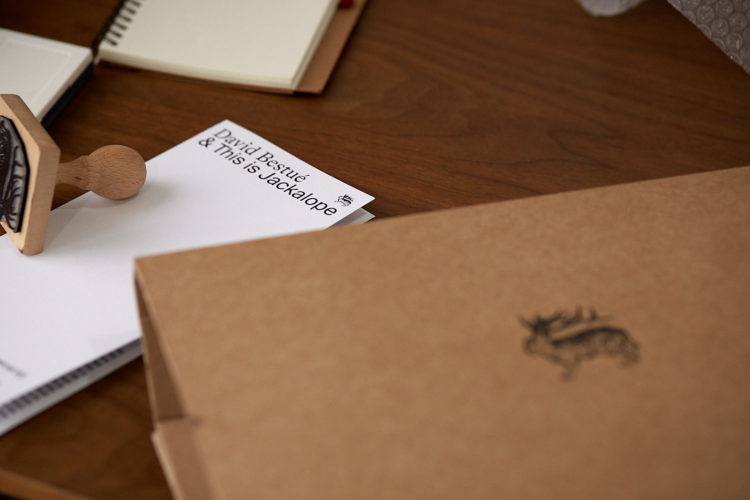

Production: Xflash

Photographs: MuroAzul

David Bestué (Barcelona 1980) is an artist interested in the confluence between sculpture, poetry and architecture. Among his recent solo exhibitions are De perder un nombre (Diputación de Huesca, 2020), Miramar (Pols, Valencia, 2019), ROSI AMOR (Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2017) and Realisme (La Capella, Barcelona, 2015). He has also participated in group exhibitions such as Infinite Sculptures (Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, 2020), among others. His latest books are Historia de la Fuerza (Poodle, 2017) and Viaplana y Piñón (Puente editores, 2018).

TIJ: The piece Aníbal / Salamanca takes its name directly from its relation to the figure of the poet Aníbal Nuñez and his link with the Salamanca area. Can you tell us a bit about both relationships and why you were interested in working with them?

David Bestué: The point of departure, as you pointed out, is that relationship between the poet and Salamanca, and how, in his successive books, he documents social and scenic changes to the location and, by extension, to Castile, clearing away the clichés that had smothered that area for the first half of the twentieth Century. Its an exquisite yet, at the same time, melancholic poetry, torn to shreds because it somehow manages to discuss the difficulty of dealing with a territory in a lyrical way at that time (I am referring to the 1970s and 1980s), which was suffering the consequences of very aggressive modernization. This is why wheat, reeds and lilies appear alongside ruins, cranes and materials such as polyvinyl in Aníbal Núñez’s poetry.

TIJ: The form and materials take on a very important role in your work, in its apparent simplicity, a great amount of information and meaning accumulates. In Aníbal/Salamanca, specifically, we find ourselves confronted by an ingot that has a solid and neutral appearance. Could you explain what data it collects in its composition and format?

David Bestué: The idea of the ingot interested me because it somehow marks a formal degree zero, a resistance to acquiring figuration in order to focus on its material content. In reality, its dimensions are set by a brick collected from Tejares, a town near Salamanca, which Núñez cites as an example of one of those picturesque places that became the city’s peripheral neighbourhoods over time. In terms of materials, I wanted to play with spaces and times that are literally taken from his poetry. Regarding the times, in each block there is a flower and fruit from the same apple tree picked at two different times in the year. With respect to the spaces, the flower and fruit are mixed with mud from the river Tormes, whose form comes, as I said earlier, from a Tejares brick located on the town’s shore. For me, this piece will acquire full meaning when the forty copies of the edition are sold, because it will be as if the tree contained in it will have been dispersed.

TIJ: We see similarities between your work–in the visual arts–and Aníbal Núñez’s poetry. Both of them are formed as pieces of a balanced asepticity that transmits a gesture or feeling with an unusual force that can take on a human, political or social nuance. What was it that attracted you to the figure of Aníbal Núñez initially? Are there any specific verses or is there a particular poem that you still have in your head?

David Bestué: I suppose that what attracted me to him was the already discredited image of the poet in relation to the mythical space of nature and the poetic form itself. In his texts, a mismatch between reality and language repeatedly appears, and I think he tries to amend that by plunging words into the territory and the specific elements that comprise it. He mixes ruins with words and the names of flowers in a style somewhere between the lyrical and the ironic, between the innocent and the snide. Something I can identify with quite a lot. The way he tries to document the real through the poetic form, and the way he knows that this form is incomplete and useless, is similar to my way of understanding sculpture. That’s why, when trying to deal with his work in a material sense, I can only follow the trail of his walks and offer a little bit of the specific place that he describes through language. I find it difficult to sum up his work in a few verses or a poem and would encourage people to enjoy them as a whole. It’s true that after I read it, I had a few words knocking around in my head, an image of them. There are a couple of verses that have been stuck in my head since the first time I read them: “How the sun had come this morning/what a showoff”. I don’t know why, but I love them. I imagine Aníbal as being very happy at that moment, walking early in the morning, all the light suddenly shining on his face, like an explosion.