You, the World and I

A Solo Show by Jon RafmanYou, the World and I

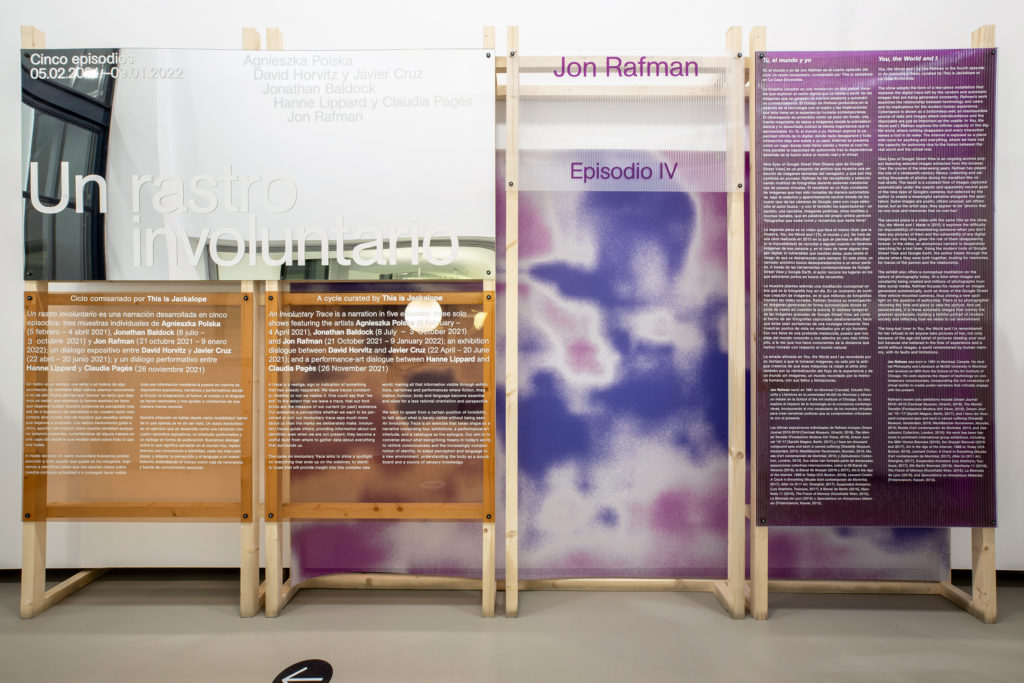

You, the World and I by Jon Rafman is the fourth episode in An Involuntary Trace, curated by This is Jackalope at La Casa Encendida.

The show adopts the form of a two-piece installation that explores the digital trace left by the random and automatic images that are being generated constantly. Rafman’s work examines the relationship between technology and users and its implications for the modern human experience. Of particular interest on this occasion is the artist’s ability to disclose an invisible story: that which is told by the images of ourselves that circulate on the internet but in which we are not identified.

Exhibition Design: Pablo Ferreira

Begoña Solís / La Casa Encendida, 2021

Exhibition Design: Pablo Ferreira

Begoña Solís / La Casa Encendida, 2021

Exhibition Design: Pablo Ferreira

Begoña Solís / La Casa Encendida, 2021

Exhibition Design: Pablo Ferreira

Begoña Solís / La Casa Encendida, 2021

Exhibition Design: Pablo Ferreira

Begoña Solís / La Casa Encendida, 2021

You, the World and I

You, the World and I by Jon Rafman is the fourth episode in An Involuntary Trace, curated by This is Jackalope at La Casa Encendida.

Graphic Design: Otro Bureau

The show adopts the form of a two-piece installation that explores the digital trace left by the random and automatic images that are being generated constantly. Rafman’s work examines the relationship between technology and users and its implications for the modern human experience. Of particular interest on this occasion is the artist’s ability to disclose an invisible story: that which is told by the images of ourselves that circulate on the internet but in which we are not identified.

Cyberspace is shown as a bottomless well, an inexhaustible source of data and images where overabundance and the disposable are just as important as the usable. In You, the World and I, Rafman explores the infinite capacity of the digital world, where nothing disappears and every interaction leaves a trail in its wake. The internet is exposed as a place with room for anything and everything, where we have lost the capacity for autonomy due to the fusion between the real world and the virtual one.

In 2007, Google launched Google Street View, a tool that captured photos of the whole world to make it easier for users to browse Google Maps. One year later, in 2008, Rafman began working on Nine Eyes of Google Street View, an ongoing archive project featuring selected images extracted from the browser. Over the course of the intervening years, Rafman has played the role of a nineteenth-century flâneur, collecting and selecting thousands of photos during his marathon-like virtual strolls. The result is a constant flow of images captured automatically under the aseptic and apparently neutral gaze of the nine eyes of Google’s cameras, but selected by the author to create a meaningful narrative alongside the spectators. During the process, we become acutely aware that this human consciousness and the ability to make associations and produce meaning have been compromised. Some images are poetic, others unusual, yet others banal, but as the artist says, they appear to be “photos that no one took and memories that no one has”. Ultimately, they are traces that create a sense of nostalgia, yearning and loss, evoking old family snapshots. This tension reflects our modern experience, always mediated by technology and rooted in the time lapse generated between reality and the virtual world.

Bego Solís, La Casa Encendida 2021

The second piece is a video with the same title as the show, You, the World and I. Made in 2010, it explores the difficulty (or impossibility) of remembering someone when you don’t have any pictures of them and the vulnerability of any digital images you may have, given the risk of them disappearing forever. In the video, an anonymous narrator is desperately searching for a lost lover. Using the modern tools of Google Street View and Google Earth, the author trawls through the places where they were both together, looking for memories, for traces of the person and the relationship. We follow him through a geographic and social expedition that mixes Google satellite images with 3D representations of historic places—like Stonehenge and Machu Picchu—created by users of the tool, and Google Street View panoramas of the couple’s favourite holiday places. The author’s exhaustive quest finally bears fruit when he finds an image to hold on to as proof of the existence of his past experience. In his text for Rafman’s exhibition at Sprüth Magers gallery, Ned Beauman spoke about the idea that “time has almost ceased to tick”. In this case, that same idea freezes and condenses an entire relationship in a screenshot that replaces all other experiences and memories.

Bego Solís, La Casa Encendida 2021

By constantly interacting with the world through the mediation of technology, could it be that our narrator—and we ourselves—have unwittingly become more distant from the world? Do we always need an image to trigger our memories? All of this pushes us into the abyss of computational thinking and the philosophy of solutionism, where we prioritise efficiency and the end result over learning and the slow digestion of experience. In New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, James Bridle states that “the abundance of information and the plurality of worldviews now accessible to us through the internet are not producing a coherent consensus reality, but one riven by fundamentalist insistence on simplistic narratives, conspiracy theories and post-factual politics”. One of the dangers of this superabundance of information is the difficulty of distinguishing between fake and real data. We are gradually coming to realise that what we hoped would add clarity to the world through fast, transparent and universal access to information has become a double-edged sword where opacity and darkness prevail.

The exhibit also offers a conceptual meditation on the nature of photography today. At a time when images are constantly being created and millions of photographs inundate social media, Rafman focuses his research on images generated automatically, such as those of the Google Street View vehicle-mounted cameras, thus shining a new spotlight on the question of authorship. There is no photographer choosing the time and place to take the picture. And yet, paradoxically, it is these automatic images that convey the greatest spontaneity, building a faithful portrait of modern society and reflecting how we relate to our environment.

The new technological age has plunged us into a world dominated by the appearance of “hyper-objects”, i.e. things that surround, envelop and ensnare us but are literally too big for us to view in their entirety, so all we perceive is the traces they leave on other objects. This is precisely how the World Wide Web works. The concept of the sublime suffuses Rafman’s work, from the Kantian and romantic conception associated with nature to the technological conception described during the postmodern period by Frederic Jameson. As Bridle points out, “Today the cloud is the central metaphor of the internet: a global system of great power and energy that nevertheless retains the aura of something noumenal and numinous, something almost impossible to grasp.”

Rafman seems to challenge the separation we uphold between the subjectivity that exists through our bodies and that of our screens. The space-time framework is completely distorted, rendering orientation through conventional parameters much more difficult. In this work, the world is broken down into photo stills and time passes unevenly (due to the need for constant updates).

Rafman seems to challenge the separation we uphold between the subjectivity that exists through our bodies and that of our screens. The space-time framework is completely distorted, rendering orientation through conventional parameters much more difficult. In this work, the world is broken down into photo stills and time passes unevenly (due to the need for constant updates).

At the beginning of 2021, an article in The New Yorker examined how the pandemic and lockdown had increased the popularity of Google Street View. During the time when we were confined to our homes, cities and countries, Google Street View enabled us to take virtual walks in places that we were unable to visit physically. This same phenomenon also boosted the use of initiatives like Random Street View and MapCrunch, two websites where users can play at being online explorers: a simple click of the mouse transports you to a random point on the globe where you can begin your virtual tour, applying area filters if you want.

The time-lapse of the images recorded in Google Street View, coupled with the fact that they are randomly captured, imbues them with an inherent nostalgia. They show us perspectives that are not mediated by the human eye, filling us with a profound melancholy as we are separated from the known world and transported to a more inhospitable one, and reminding us how distant we have grown from the natural world.

The long-lost lover in You, the World and I is remembered for her refusal to let anyone take pictures of her, not only because of the age-old belief of pictures stealing your soul but because she believed in the flow of experience and a world without images, a world remembered by human memory, with its faults and limitations.

—

1 James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (London: Verso, 2018).

2 Ibid., p. 17.

3 Sophie Haigney, “The Pandemic-induced Popularity of Google Street View”, The New Yorker, 6-2-2021 (https://www.newyorker.com/culture/rabbit-holes/the-pandemic-induced-popularity-of-google-street-view).

—

Jon Rafman was born in 1981 in Montreal, Canada. He studied Philosophy and Literature at McGill University in Montreal and received an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work explores the impact of technology on contemporary consciousness, incorporating the rich vocabulary of virtual worlds to create poetic narratives that critically engage with the present.

Rafman’s recent solo exhibitions include Dream Journal 2016−2019 (Centraal Museum, Utrecht, 2018), The Mental Traveller (Fondazione Modena Arti Visive, 2018), Dream Journal ’16−’17 (Sprüth Magers, Berlin, 2017), and I have ten thousand compound eyes and each is named suffering (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2016; Westfälischer Kunstverein, Munster, 2016; Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 2015; and Zabludowicz Collection, London, 2015). His work has been featured in prominent international group exhibitions, including the 58th Venice Biennale (2019), the Sharjah Biennial (2019 and 2017), Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today (ICA Boston, 2018), Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything (Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 2017), After Us (K11 Art, Shanghai, 2017), Suspended Animation (Les Abattoirs, Toulouse, 2017), Berlin Biennial 9 (2016), Manifesta 11 (2016), The Future of Memory (Kunsthalle Wien, 2015), La Biennale de Lyon (2015), and Speculations on Anonymous Materials (Fridericianum, Kassel, 2013).